One of the projects the Museum staff and volunteers are working on during lockdown is digitising and transcribing our vast collection of oral history interviews, recorded in the late 1980's and early 1990's. Fortunately, one of the interviewers stuck around as well!

Here our Assistant Curator Dave Gwyer recounts the original project he worked on and reveals some fascinating anecdotes that he's rediscovered...

In November 1987 I joined a government-funded job creation scheme, based at the newly-opened Pontypridd Historical and Cultural Centre – now Pontypridd Museum. There were six of us at the start and part of our work was to find and interview some of the town’s older residents, recording their memories for posterity.

None of us had ever done any oral history before and we made all the basic mistakes, from forgetting to switch on the tape recorder, to failing to simply shut up and just let the interviewees speak for themselves. But we eventually put together a collection of rough and ready recordings which were supposed to be transcribed via the flickering green and black screen of the one Amstrad 8256 PCW we shared. Not all of them were finished, and over recent weeks in lockdown I’ve been revisiting the tapes (played on the original 1987 Philips cassette recorder!), and finally getting around to transcribing them.

It’s a slightly surreal and disturbing experience listening to your own voice from half a lifetime ago. Listening to the voices of the interviewees has been a pleasure though, albeit tinged with sadness when it dawns on you that they’ve all gone now, their voices echoing down the years, reminding us of the part that each of them played in the town’s story.

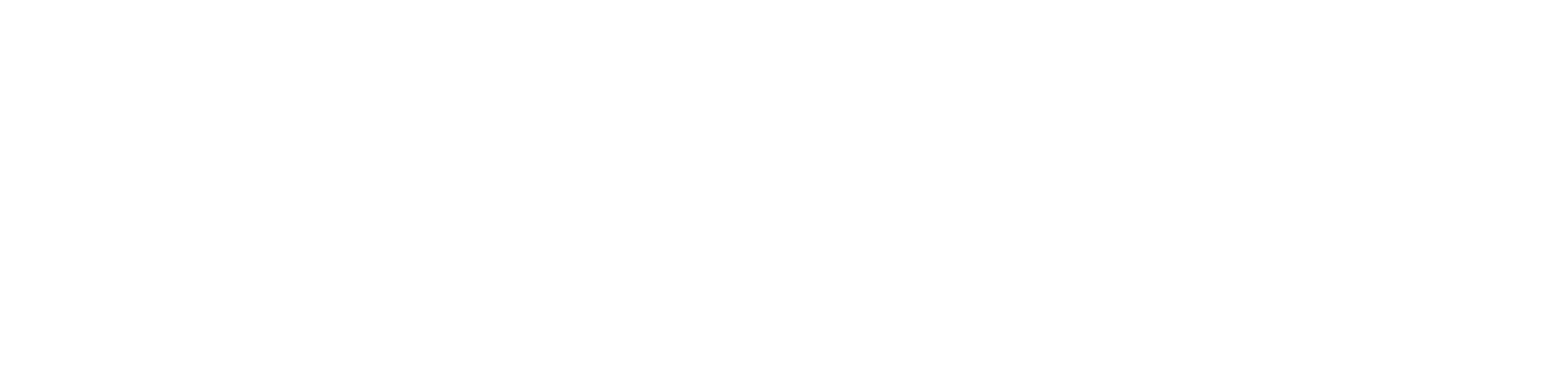

Many of the people interviewed were in their late 80s at the time. Stop to think about that. They saw and experienced Pontypridd before the First World War, when the town was booming and in its Edwardian heyday. They lived through the polar opposite of that, struggling through the Depression of the ‘20s and ’30s with its strikes, unemployment, and soup kitchens. You can read about all this in countless history books, but here are the people who lived through it and came out the other side unbowed.

People like Gertie Williams (née Britton) who was born in 1900, left school at 14, and was put into service because her mother couldn’t afford further education. Each day she'd walk from Treforest to the top of Berw Road by 8am to spend her day cleaning for just 1 shilling 6 pence per week (7 new pence).

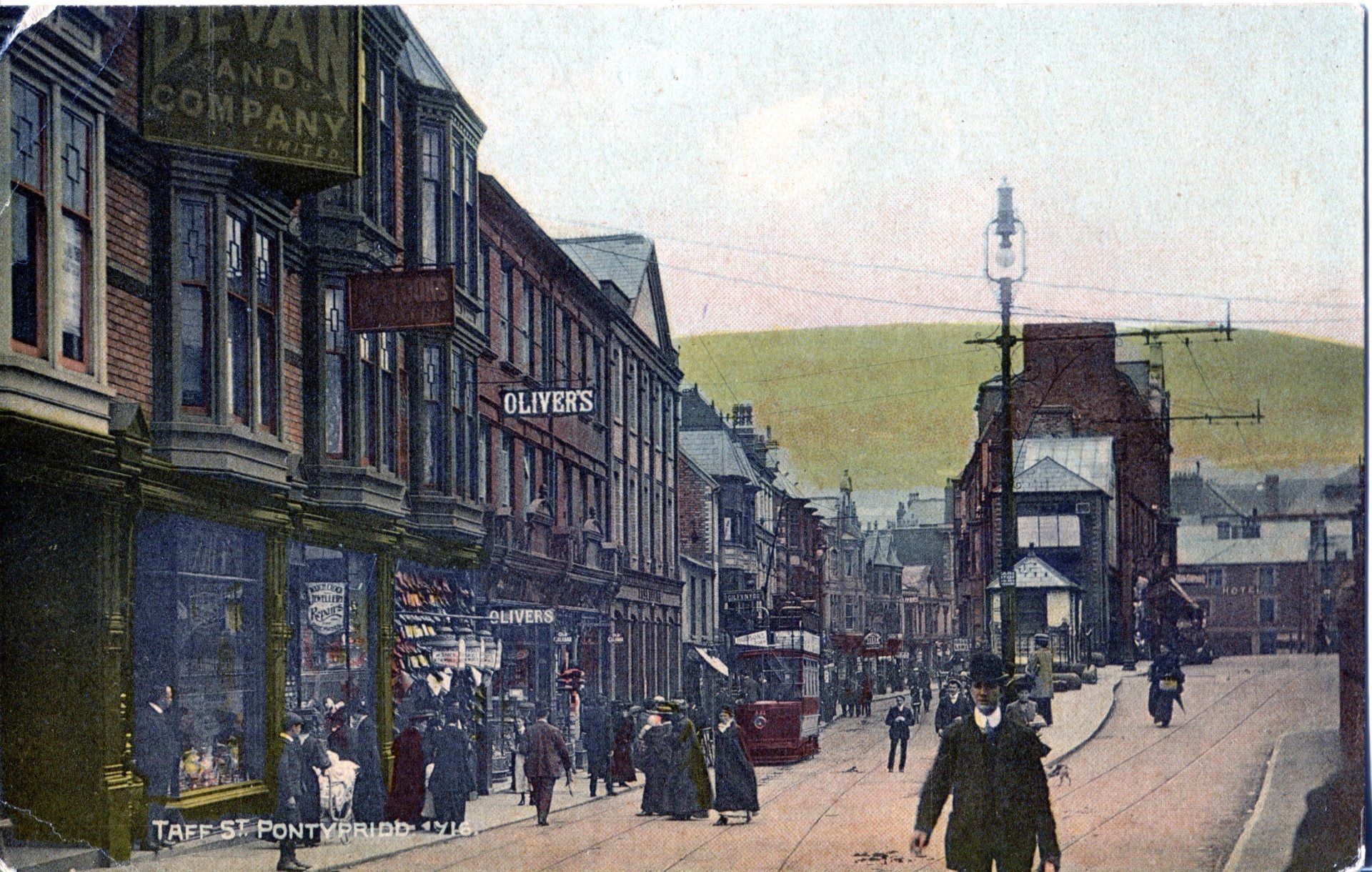

For women like Gertie, the First World War opened up opportunities. With so many men away fighting, some of the jobs they did became available to women. At 17, Gertie went to Glyntaff tramcar depot and asked the superintendent, ‘I’ve come for a job sir, I want to be a conductress like my friend .’ The superintendent had his doubts because Gertie was so small, but her enthusiasm won him over.

Looking back, she recalled the 3 years she spent on the ‘cars’ as the happiest time of her working life, and the increased wages she brought home meant her mother ‘thought she was in wonderland.’ She even met her future husband on her trams, a young collier boy who worked at the Great Western pit on his way to brass band rehearsals.

Other memories remind you that Pontypridd is not an old town and take you back to when parts of it were still largely rural. Mrs Pugh from Hawthorn, who lost her sight in her 70s, recalled the farms which dotted the landscape from Upper Boat to Hawthorn, with the names of each of the families associated with them.

She lived through the Depression when her husband was out of work for long periods and the family had to exist on unemployment benefit of 1 pound 6 shillings a week (20 shillings to a pound and a shilling is 5 new pence). She also provided an intriguing snippet which needs following up post-lockdown.

Back in 1989 she mentions a story published in the Pontypridd Observer, in which a women from Duffryn Avenue, Rhydyfelin, called Mrs Williams, allowed the burgeoning Greggs bakery chain (originally based in Newcastle upon Tyne) to use her personal recipe for Welsh cakes. Greggs has expanded massively since the late 1980s and now distributes Welsh cakes nationwide from its factory at Treforest Estate. It would be wonderful to think they are still made to this local recipe.

Whatever hardships the decade brought, some tales from the 1920s can still raise a smile. Maldwyn Davies lived on the Graig. He loved sport and talked at length about the town's sporting history, particularly as it related to Taff Vale Park. Today this simple playing field, sandwiched between the river Taff and Parc Lewis School in Treforest, shows few signs that for the first 30 years of the 20th century it was one of the most important sporting arenas in Wales.

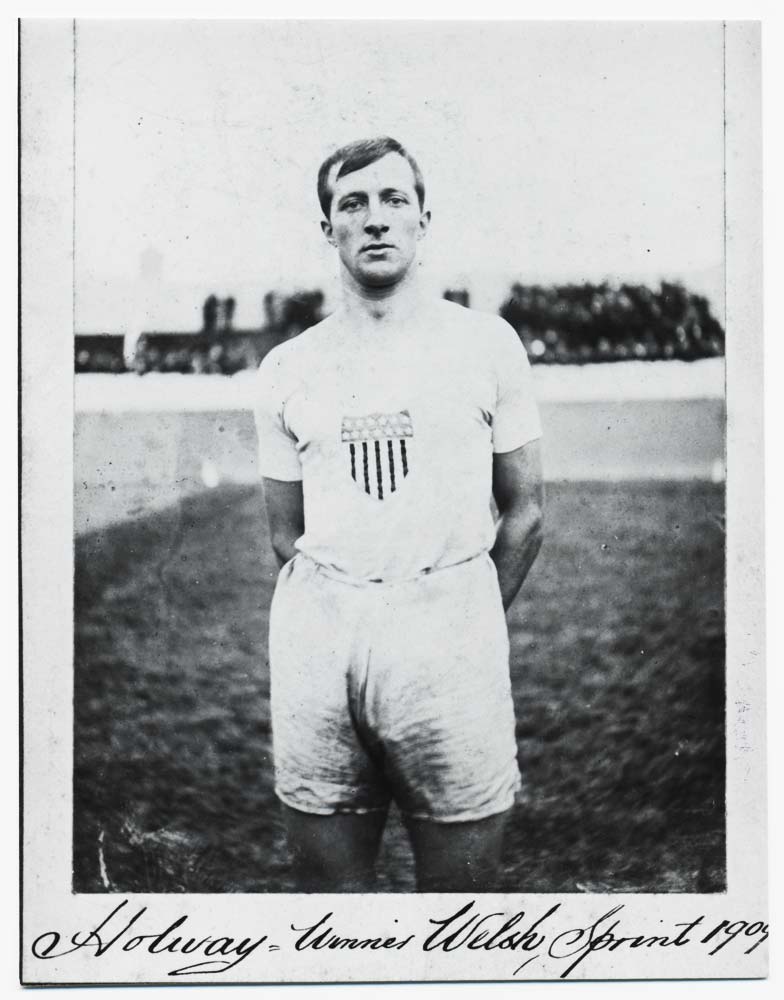

During that time the most famous event held there was the Welsh Powderhall Sprint, a professional race named after the stadium in Edinburgh where the original Scottish Powderhall was run. From 1903 to 1929 (after this a rival Powderhall event set up in Caerphilly for five years) it attracted the best athletes from Britain and around the world - runners such as the American Charles Holway, who won in 1909. Holway was one of the few men to defeat the legendary Australian world record holder, Jack Donaldson, the 'Blue Streak'.

Maldwyn kept in touch with Holway for many years, even securing a substitute Powderhall winner's gold medal to replace the one Holway had lost during the Depression. Maldwyn's proudest moment came in 1929 when his brother Bryn won the Powderhall. The nationwide fame of the race meant that Bryn's photograph was soon plastered over railway siding billboards as far afield as London, with the reassuring message for the masses that he trained on Horlicks!

While the prestige of winning the Welsh Powderhall meant that those in with a chance competed fairly, others lower down the pecking order were not above a spot of skulduggery to fleece the bookies. Some, who were good enough to win a heat, might put lead weights in their running shoes, slowing them enough for the next best runner to win - having already bet that man themselves. Maldwyn recalled that during the '20s, organised race gangs would descend on Treforest for the big sporting meets. They'd require a 'voluntary' contribution from the field bookies as protection from any trouble (i.e. from them!). Those who refused to pay up might not be seen for a spell afterwards, while they became better acquainted with hospital food.

The images he conjured brought to mind a scenario pitched somewhere between the menace of Graham Green's 'Brighton Rock', and the larger than life, loveable, characters of Damon Runyon's New York-set short stories, but with the accents more Broadway, Treforest than Broadway, Manhattan.

These snapshot memories add immeasurably to the colour and texture of Pontypridd's history. They remind us that we all have a story to tell and that we all belong to a greater community. In these troubled days that's a hopeful thought to hang on to. If you read this and think you can expand on these or any other local stories, we'd certainly welcome your contribution. You never know, perhaps we'll be interviewing you one of these days!

Share

RECENT POSTS

Ydych chi’n chwilio am weithgaredd hwyliog sy’n rhad ac am ddim yn Amgueddfa Pontypridd yn ystod gwyliau hanner tymor mis Chwefror? O Dydd Llun 24 Chwefror ymunwch â ni i fwynhau Llwybr Tourmaline a’r Amgueddfa Rhyfeddodau! Chwiliwch am Tourmaline, ei ffrindiau ac amrywiaeth o arteffactau hudol sy’n cuddio yn yr amgueddfa – ac yna lluniwch eich Amgueddfa Rhyfeddodau eich hun! Bydd y tri chynllun buddugol yn ennill bwndel lyfrau Tourmaline a Thocyn Celf Cenedlaethol (a phlant) drwy garedigrwydd @artfund. Cwblhewch y llwybr i dderbyn sticer!